Isoprenoids: 3. Other Linear Membrane-Associated Isoprenoids

Terpenes

(isoprenoids) are one of the most varied and abundant of the natural products produced by animals, plants and bacteria.

They are generally defined on the basis of their biosynthetic derivation from isoprene units (C5H8),

with 55,000 different types characterized to date according to a recent estimate.

By some definitions (see my web page on Nomenclature), all isoprenoids should be classified

as ‘lipids’, from simple monoterpenes such as geraniol, which is derived from two prenol units, to complex polymers such

as natural rubber.

Practical considerations force me to restrict the range of lipid classes that can be described in detail in these web pages,

and here, only those isoprenoids that have a role in the structure and metabolism of cellular membranes are discussed,

i.e., plastoquinone, ubiquinone (coenzyme Q), phylloquinone and menaquinone (vitamin K), dolichol and polyprenols, undecaprenyl phosphate

and lipid II, and farnesyl pyrophosphate, together with some key biosynthetic precursors.

In all of these, there is a linear isoprene chain.

Although tocopherols and tocotrienols (vitamin E) and retinoids (vitamin A)

are relevant to this topic, these are large subjects best described in separate web documents.

Of course, sterols are also isoprenoids.

Terpenes

(isoprenoids) are one of the most varied and abundant of the natural products produced by animals, plants and bacteria.

They are generally defined on the basis of their biosynthetic derivation from isoprene units (C5H8),

with 55,000 different types characterized to date according to a recent estimate.

By some definitions (see my web page on Nomenclature), all isoprenoids should be classified

as ‘lipids’, from simple monoterpenes such as geraniol, which is derived from two prenol units, to complex polymers such

as natural rubber.

Practical considerations force me to restrict the range of lipid classes that can be described in detail in these web pages,

and here, only those isoprenoids that have a role in the structure and metabolism of cellular membranes are discussed,

i.e., plastoquinone, ubiquinone (coenzyme Q), phylloquinone and menaquinone (vitamin K), dolichol and polyprenols, undecaprenyl phosphate

and lipid II, and farnesyl pyrophosphate, together with some key biosynthetic precursors.

In all of these, there is a linear isoprene chain.

Although tocopherols and tocotrienols (vitamin E) and retinoids (vitamin A)

are relevant to this topic, these are large subjects best described in separate web documents.

Of course, sterols are also isoprenoids.

Of these, lipoquinones, i.e., plastoquinone, ubiquinone (coenzyme Q), phylloquinone and menaquinone (vitamin K), are distinguished by a polar redox-active 1,4‑quinone headgroup and a hydrophobic substituent consisting of a lengthy isoprenoid unit. They are located in cellular membranes where they act as electron carriers to transfer electrons between membrane-bound protein complexes within electron transport chains, ultimately producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Although the functions are similar, the structures of the headgroups vary among bacteria, plants and animals,

For the biosynthesis of the isoprene units that are the precursors for the biosynthesis of isoprenoids, i.e., isopentenyl pyrophosphate and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, there are two basic mechanisms, i.e., the mevalonate pathway, which is located in the cytosol of the cell and is described in our web page on cholesterol, and the non-mevalonate pathway found mainly in the plastids of plants and discussed in our web page on plant sterols.

1. Phytol

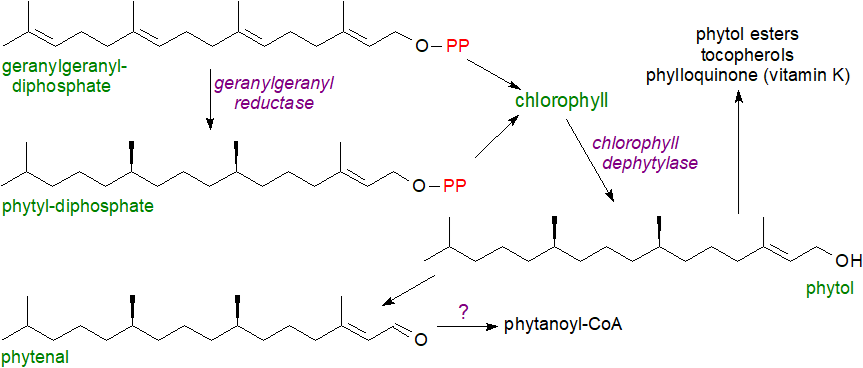

Phytol or (2E,7R,11R)-3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol, i.e., with 20 carbons in a 16-carbon chain and one double bond, is an acyclic diterpene alcohol, which is synthesised in large amounts in plants as an essential component of chlorophyll, the photosynthetic pigment in plants and algae. Geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthesised in chloroplasts via the 4-methylerythritol-5-phosphate (non-mevalonate) pathway is the primary precursor of phytol following reduction of three double bonds by geranylgeranyl reductase, and this can occur before or after attachment to chlorophyll, depending upon species. Chlorophyll dephytylase (CLD1) is the enzyme in plants responsible for chlorophyll hydrolysis and release of phytol.

|

| Figure 1. Phytol biosynthesis and catabolism. |

Little free phytol is present in plant tissues, although some phytol esters of fatty acids may occur, and bell peppers and rocket salad are rich sources under normal conditions, but greater amounts are produced when plants are stressed as during nitrogen deprivation or in senescence, when chlorophyll is degraded. Fatty acids are released from glycerolipids, and phytol ester synthases (PES1 and PES2 in Arabidopsis) are induced as part of a general detoxification and recycling process. Phytol as its diphosphate is utilized for the synthesis of tocopherols (vitamin E) and phylloquinol (vitamin K - see below), and in some plants, the precursor geranylgeraniol (and its fatty acid ester) occur in small amounts. The last is the biosynthetic precursor of tocotrienols and the highly unsaturated carotenoids (and thence of retinoids). Phytenal has been isolated as an intermediate in the catabolism of phytol in plants, but further steps are uncertain although phytanoyl-CoA is one metabolite detected in stressed plants. As phytenal is a highly reactive electrophile and potentially toxic via its interaction with proteins, competing pathways limit its accumulation.

In ruminant animals, chlorophyll is hydrolysed by microorganisms in the rumen with release of free phytol, but this reaction does not occur in humans, although some phytol may be ingested with plant foods either in free form or as phytol esters and can be absorbed from the intestines. Within animal tissues, phytol is converted to phytanic acid, which can be incorporated into glycerolipids or further metabolized, while in shark liver, it is reduced to pristane. Phytol and/or its metabolites have been reported to activate the transcription factors PPARα and retinoid X receptor, and in mice, oral phytol induces a substantial proliferation of peroxisomes in many organs.

2. Plastoquinone

Plastoquinone is a terpenoid quinone found in cyanobacteria and plant chloroplasts, and it is produced

in plants by analogous biosynthetic pathways to those of tocopherols in the inner chloroplast envelope with solanesol diphosphate as the

biosynthetic precursor of the side chain (although in cyanobacteria, there may be a somewhat different mechanism).

The molecule is sometimes designated - 'plastoquinone-n' (or PQ-n), where 'n' is the number of isoprene units, which can vary from 6 to 9.

Plastoquinone is a terpenoid quinone found in cyanobacteria and plant chloroplasts, and it is produced

in plants by analogous biosynthetic pathways to those of tocopherols in the inner chloroplast envelope with solanesol diphosphate as the

biosynthetic precursor of the side chain (although in cyanobacteria, there may be a somewhat different mechanism).

The molecule is sometimes designated - 'plastoquinone-n' (or PQ-n), where 'n' is the number of isoprene units, which can vary from 6 to 9.

Plastoquinone has a crucial role in photosynthesis, by providing an electronic connection between photosystems I and II to generate an electrochemical proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane and provide energy for the synthesis of ATP. The resulting reduced dihydroplastoquinone (plastoquinol) transfers further electrons to the photosynthesis enzymes before being re-oxidized by a cytochrome complex. With photosystem II from cyanobacteria, X-ray crystallography studies show two molecules of plastoquinone forming two membrane-spanning branches. Plastoquinone is a comparable antioxidant to the tocopherols, protecting against excess light energy and photooxidative damage, and in thylakoid membranes, plastoquinol can scavenge superoxide with production of H2O2. In carotenoid biosynthesis, plastoquinone is a cofactor participating in desaturation of phytoene, and it is the biosynthetic precursor of plastochromanols (see our web page on tocopherols). With these many different functions, plastoquinone connects photosynthesis in plants with metabolism, light acclimation and stress tolerance.

Plastoquinone-9, together with phylloquinone, tocopherol and plastochromanol-8, is stored in plastoglobuli, lipoprotein-like micro-compartments, which enable exchange with the thylakoid membrane and are utilized in chlorophyll catabolism and recycling. It has been suggested that the redox state of the plastoquinone pool is the main sensor in chloroplasts that initiates many physiological responses to changes in the environment and in particular to those related to light intensity by regulating the expression of chloroplast genes. Mono-acyl plastoquinol (with 16:0 and 18:0 fatty acids) has been characterized as a constituent of cyanobacteria and algae, possibly as a storage form (it may have been mis-identified in early analyses as a triacylglycerol with which it co-chromatographs).

3. Ubiquinone (Coenzyme Q)

The ubiquinones, which are also known as coenzyme Q (CoQ) or mitoquinones, have obvious biosynthetic and metabolic relationships to plastoquinone, and they are found in all the domains of life (hence the name). They have a 2,3‑dimethoxy-5-methylbenzoquinone nucleus and a side chain of six to ten isoprenoid units; the human form illustrated below has ten such units (coenzyme Q10), i.e., it is 2,3‑dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-decaprenyl-1,4-benzoquinone, while that of the rat has nine, Escherichia coli has eight and Saccharomyces cerevisiae has six, while in plants, ubiquinones tend to have nine or ten isoprenoid units. Forms with a second chromanol ring (ubichromanols), resembling the structures of tocopherols, are produced as reductive cyclization products of ubiquinone (but not in animal tissues), and they act as radical scavenging antioxidants. Because of their hydrophobic properties, ubiquinones are located entirely in membrane bilayers in most eukaryote organelles, probably at the mid-plane.

Ubiquinones are synthesised de novo in mitochondria in most cells in animal, plant and bacterial tissues by a complex sequence of reactions from the essential amino acid phenylalanine and then via tyrosine to generate p-hydroxybenzoic acid. In plants, many of these reactions occur via p‑coumarinic acid in the peroxisomal compartment, although there is a separate pathway via kaempferol as an intermediate. p‑Hydroxybenzoic acid is the precursor that is condensed with the polyprenyl unit (from the cholesterol synthesis pathway) via a transferase, and this is followed by decarboxylation, hydroxylation and methylation steps, depending on the organism. In E. coli, biosynthesis does not occur in a membrane environment as had been thought, but rather, the seven proteins that catalyse the last six reactions of the biosynthetic pathway following the attachment of the isoprenoid tail form a stable complex or metabolon in the cytoplasm so enabling modification of the hydrophobic substrates in a hydrophilic environment.

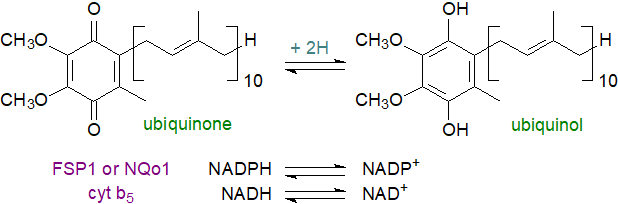

In mitochondria, coenzyme Q is present both as the oxidized (ubiquinone) and reduced (ubiquinol) forms. Ubiquinones are crucial components of the respiratory electron transport system, possibly as part of super-molecular complexes, taking part in the oxidation of succinate or NADH via the cytochrome system to generate the protonmotive force used by the mitochondrial ATPase to synthesise ATP. In this process in which ubiquinone is reduced to ubiquinol with the participation of enzymatic systems, CYB5R3, NQO1 and cytochrome P450 reductases, in NADH- and NADPH-driven reactions, coenzyme Q transfers electrons from the various primary donors, including complex I, complex II and the oxidation of fatty acids and branched-chain amino acids to the oxidase system (complex III), while simultaneously transferring protons to the outside of the mitochondrial membrane to cause a proton gradient across the membrane. Ubiquinone is thus essential to the cycle that generates the proton motive force to drive ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation. In yeast, one coenzyme Q binding protein (COQ10) and in humans two related proteins (COQ10A and COQ10B) may serve as chaperones or transporters during this process.

|

| Figure 2. Ubiquinone - conversion to ubiquinol. |

In its reduced form (ubiquinol) in non-mitochondrial cellular membranes and plasma lipoproteins, it acts as an endogenous antioxidant, the only lipid-soluble antioxidant to be synthesised endogenously. It inhibits lipid peroxidation in membranes and serum low-density lipoproteins, and it may protect membrane proteins and DNA against oxidative damage. The ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) replenishes ubiquinol, and this acts protectively by combating the lipid peroxidation that drives ferroptosis. The mechanism involves recruitment of FSP1 to the plasma membrane following myristoylation, where this is an oxidoreductase that reduces ubiquinone to ubiquinol, which acts as a lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidant to halt the propagation of lipid peroxides. In this manner, it regulates cellular redox status and cytosolic oxidative stress and thereby is a controlling factor in apoptosis. Other NAD(P)H dehydrogenases that are CoQ reductases include cytochrome b5 reductase and NQo1 (NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase).

Although ubiquinone

is only about one tenth as efficient as an antioxidant as vitamin E (α-tocopherol), it is able to stimulate

the latter by regenerating it from its oxidized form back to its fully reduced state (with vitamin C).

On the other hand, ubiquinones and tocopherols can apparently exhibit either cooperative or competitive effects under different physiological

conditions.

In bacteria and other prokaryotes, ubiquinones participate in many redox reactions, notably in the respiratory electron

transport system but also in other enzyme reactions that require electron donation, including the formation of disulfide bonds.

Although ubiquinone

is only about one tenth as efficient as an antioxidant as vitamin E (α-tocopherol), it is able to stimulate

the latter by regenerating it from its oxidized form back to its fully reduced state (with vitamin C).

On the other hand, ubiquinones and tocopherols can apparently exhibit either cooperative or competitive effects under different physiological

conditions.

In bacteria and other prokaryotes, ubiquinones participate in many redox reactions, notably in the respiratory electron

transport system but also in other enzyme reactions that require electron donation, including the formation of disulfide bonds.

In complete contrast, mitochondrial coenzyme Q has been implicated in the production of reactive oxygen species by formation of superoxide from ubisemiquinone radicals, and in this way, it is responsible for causing some of the oxidative damage behind some degenerative diseases, i.e., it acts as a pro-oxidant in this circumstance. It is most abundant in organs with a high metabolic rate such as the heart, kidneys and liver.

Coenzyme Q has many other functions that are not related directly to its antioxidant properties. Some coenzyme Q is used in mitochondria by enzymes that link the mitochondrial respiratory chain to other metabolic pathways, including fatty acid β‑oxidation as an electron acceptor, nucleotide biosynthesis de novo, amino acid oxidation (glycine, proline, glyoxylate and arginine), and detoxification of sulfide. It is a regulator of mitochondrial permeability, and in relation to pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis, it is required for DNA replication and repair. In this manner, coenzyme Q may indirectly modulate metabolic pathways located outside the mitochondria. There are suggestions that coenzyme Q can take part in redox control of cell signalling and gene expression and in particular to repress the expression of inflammatory genes. In relation to its anti-inflammatory properties, clinical studies suggest that dietary supplementation with coenzyme Q10 reduces the levels of the inflammatory mediators C‑reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) to a significant degree.

The length of the side chain is important, as studies with the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans depleted in UQ-8 demonstrated that the longer-chain UQ-9 and UQ-8 enable normal growth and behaviour, while shorter-chain UQ-7 and UQ-6 sustain continuous growth but fertility and development are inhibited.

Ubiquinone in food or dietary supplements is absorbed by enterocytes via a process of "passive facilitated diffusion”, probably requiring a carrier molecule, before incorporation into chylomicrons for transport to the liver. This eventually leads to elevated levels of ubiquinol in blood, especially in the LDL and VLDL lipoproteins, presumably because of reduction of the oxidized form in the lymphatic system. In consequence, there is reported to be enhanced protection against lipid peroxidation with benefits to health in relation to cardiac physiology, sperm motility and neurodegenerative diseases. Low CoQ levels in both plasma and the heart are associated with heart failure in patients, and clinical trials of dietary supplementation have shown promising results. This may be of particular relevance to the elderly or in patients on statins when endogenous synthesis declines, and similarly, early clinical trials with CoQ10 and a synthetic analogue, idebenone, have given encouraging results against various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease and others. CoQ10 is reported to be protective against ischemic stroke and to ameliorate the after effects. A CoQ10 deficiency syndrome is associated with inherited pathological diseases, defined by a decrease of the CoQ10 content in muscle and/or cultured skin fibroblasts.

4. Phylloquinone and Menaquinones (Vitamin K)

Phylloquinone or 2-methyl-3-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinone is synthesised in the inner chloroplast envelope of cyanobacteria, algae and higher plants by a mechanism analogous to that of the tocopherols, i.e., from chorismate in the shikimate pathway with a prenyl side chain derived from phytyldiphosphate. In this membrane, it is a component of the photosystem I complex where it receives an electron from the chlorophyll a acceptor molecule and then donates an electron to the membrane-associated iron-sulfur protein acceptor cluster in the complex. In an obvious parallel to the plastoquinones (above), two molecules of phylloquinone form two membrane-spanning branches, as demonstrated by X-ray crystallography studies of photosystem I from cyanobacteria. Plastoglobules associated with the thylakoid membrane act as a reservoir for excess phylloquinone and may have a role in its metabolism.

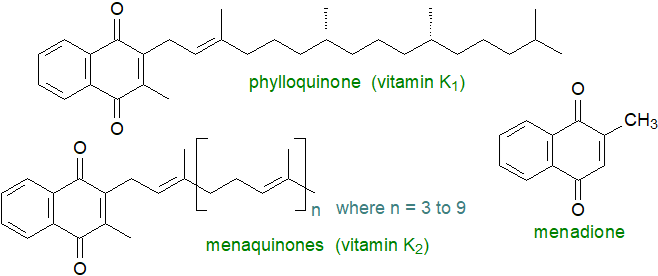

Phylloquinone is an essential component of the diet of animals and has been termed 'vitamin K1'. It must be supplied by green plant tissues, where it occurs in the range 400-700 μg/100 g, or by seed oils (75-90% of the human diet). The menaquinones, the main source of which in the human diet is cheese and yoghurt, have greater vitamin K activity (especially MK-7) and are termed 'vitamin K2'; they account for about 10-25% of the vitamin K content of the diet in developed countries. The term vitamin K is now used for a family of compounds that share a common structure, the 2‑methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone core (menadione), and have the same physiological functions. Edward A. Doisy and Henrik Dam received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1943 for their discovery of vitamin K and its chemical structure (K for 'koagulationsvitamin' in German).

|

| Figure 3. Structures of phylloquinone and menaquinones. |

The menaquinones are related bacterial products, which are components of their respiratory and photosynthetic electron transport chains with effects upon metabolism and stress tolerance. They have a variable number (4 to 10) of isoprenoid units in the tail, and they are sometimes designated ‘MK-4’ to ‘MK-10’. In contrast to phylloquinone, these are usually highly unsaturated, and instead of phytol, unsaturated isoprene units are used for their biosynthesis. In some bacteria, there are methyl or other groups attached to the naphthoquinone moiety, while myxoquinones are hydroxylated forms produced by myxobacteria. Remarkably high concentrations of menaquinones are present in membranes of some extremophiles such as the haloarchaea, where it has been suggested that they act as ion permeability barriers and as a powerful shield against oxidative stress in addition to acting as electron and proton transporters. As quinones may contribute to host colonization and virulence in pathogenic bacteria, their biosynthesis pathways are targets for the design of new antibiotics.

Vitamin K forms are absorbed in enterocytes by the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) transporter and are transported via the lymphatic system in plasma in the form of chylomicrons in a similar manner to the other fat-soluble vitamins. While vitamin K1 is taken up rapidly by the liver, vitamin K2 remains in plasma lipoproteins for much longer and may be the main source of the vitamin in peripheral tissues. Different tissues have varying storage capacities and presumably requirements for the various forms of vitamin K, and as a high proportion is excreted, there may be a requirement for a constant intake. Some dietary phylloquinone is converted to menaquinone-4 in animals, although the quantitative significance has still to be established; the mechanism involves conversion to a hydrophilic form menadione in the intestines followed by transport to tissues where a geranylgeranyl side chain is attached by a prenyl transferase.

Although it is too toxic for human nutrition, a synthetic menadione is used in animal feeds, and while it is known as 'vitamin K3', it is not a vitamin strictly speaking but a pro-vitamin in that it must first be converted to the menaquinone MK-4 in animal tissues.

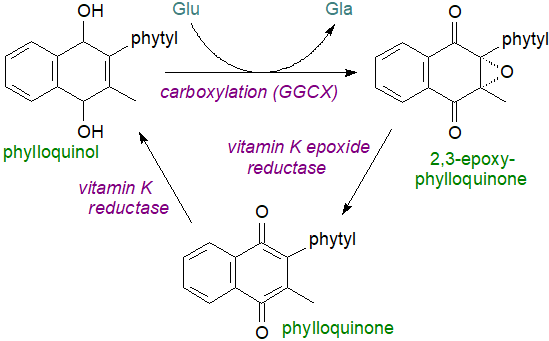

The primary role of vitamin K in animal tissues, and in the liver mainly, is to act as a cofactor for the vitamin K-dependent enzyme γ‑glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) in the endoplasmic reticulum in a post-translational γ-carboxylation of glutamate (Glu) residues in certain proteins to form γ‑carboxyglutamic acid (Gla), enabling them to bind calcium ions with a resulting conformational change as a precondition for physiological activity. In this way, prothrombin and three related proteins are stimulated to promote blood clotting, for example. Phylloquinol, by the VKORC1 enzyme located on the luminal membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum is the actual cofactor for the enzyme, and this can be re-utilized many times as part of the "vitamin K cycle", in which it donates hydrogen to the glutamic acid residue and is oxidized in the process to 2,3-epoxyphylloquinone with molecular oxygen and carbon dioxide both required for the reaction. A further enzyme, vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), regenerates phylloquinone by reduction of the epoxide in a dithiol-dependent reaction, before to complete the cycle, phylloquinone is reduced by a long-sought vitamin K reductase, now known to be ferroptosis suppressor protein‑1 (FSP1), possibly assisted by VKOR; menaquinones undergo the same cycle of reactions.

|

| Figure 4. The vitamin K cycle |

The γ-carboxylated proteins are then transported through the Golgi apparatus, where the prosequence is cleaved by a Ca2+-dependent serine proteinase in the case of prothrombin. By interfering with the last step in the vitamin K cycle, warfarin (the rodenticide) prevents blood clotting. For a similar reason, a deficiency in vitamin K results in inhibition of blood clotting and can lead to brain haemorrhaging in malnourished new-born infants, though this is not seen in adult humans presumably because intestinal bacteria produce sufficient for our needs. The enzyme FSP1, discussed above in relation to coenzyme Q, can reduce vitamin K to promote clotting but is not inhibited by warfarin, so like coenzyme Q, vitamin K is a preventative factor in ferroptosis.

It is now apparent that vitamin K2 (MK-4 especially) and vitamin K-dependent (Gla) proteins, of which 18 are now known in humans, have necessary functions in many different tissues including the central and peripheral nervous systems, where vitamin K influences sphingolipid biosynthesis in brain. Crucially, it supports calcium homeostasis and endothelial integrity, and it has a role in tissue renewal and control of cell growth. For example, osteocalcin is a γ-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein, which forms a strong complex with the mineral hydroxyapatite (calcium phosphate) of bone; it must be carboxylated to work properly and vitamin K2 is required for this reaction. Vitamin K2 regulates bone remodelling by osteoclasts to remove old or damaged bone and its replacement by new bone, and it inhibits vascular calcification. Side effects of the use of anticoagulants that bind to vitamin K can be osteoporosis and increased risk of vascular calcification, but with careful control of the dosage, vitamin K2 may be a useful adjunct for the treatment of osteoporosis, and it may reduce morbidity and mortality in the cardiovascular system, including coronary heart disease and stroke, by reducing vascular calcification.

VK1 and MK-4 act as antioxidants to prevent cellular death by inhibiting the buildup of cytotoxic reactive oxygen species in immature cortical neurons and primary oligodendrocytes while reducing the pathological consequences of ferroptosis in the liver and kidney. They are anti-inflammatory by suppressing the genes for inflammatory cytokines. It may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. Deficiencies in vitamin K have been linked to various neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease and dementia.

Excess vitamin K1 and the menaquinones are catabolized in the liver by a common degradative pathway in which the isoprenoid side chain is shortened to yield carboxylic acid aglycones such as menadiol, which can be excreted in bile and urine as glucuronides or sulfates.

5. Dolichols and Polyprenols

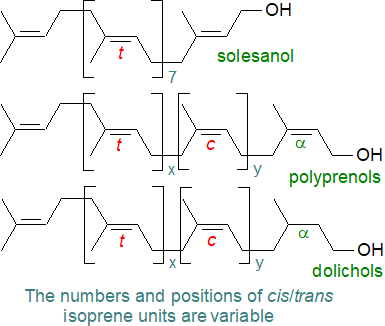

Polyisoprenoid alcohols, such as dolichols, are ubiquitous if minor components relative to the glycerolipids of membranes of most living organisms from bacteria to mammals. They are hydrophobic linear polymers, consisting of 7 to 24 isoprene residues or up to a hundred carbon atoms (or many more in plants), linked head-to-tail with a hydroxy group at one end (α-residue) and a hydrogen atom at the other (ω‑end). In polyprenols there is a double bond in the α-residue, while in dolichols (or dihydropolyprenols), this double bond is hydrogenated. Polyisoprenoid alcohols are further differentiated by the geometrical configuration of the double bonds into three subgroups, i.e., di-trans-poly-cis, tri-trans-poly-cis and all-trans.

|

| Figure 5. Formulae of polyprenols and dolichols. |

For many years, it was assumed that polyprenols were only present in bacteria and plants, mainly in photosynthetic tissues, while dolichols were found in mammals or yeasts, but it is now known that dolichols can occur at low levels in bacteria and plants, while polyprenols have been detected in animal cells. A further class of linear polyprenols has been identified in some plants and termed ‘alloprenols’, which have an unsaturated structure but with an unusual trans isoprene unit at the α-position. Solanesol is a related and distinctive plant product with trans (E) double bonds only and is a precursor of plastoquinone.

Within

a given species, a component of one chain-length may predominate, but other homologues are usually present.

The chain lengths of the main polyisoprenoid alcohols vary from 11 isoprene units in eubacteria, to 16 or 17 in Drosophila, 15 and 16 in yeasts,

19 in hamsters and 20 in pigs and humans.

In plants, the range is from 8 to 22 units, but some plants have an additional class of polyprenols with up to 40 units.

In tissues, polyisoprenoid alcohols can be present in the free form, esterified with acetate or fatty acids, and

phosphorylated or monoglycosylated phosphorylated (various forms), depending on species and tissue.

Polyisoprenoid alcohols per se do not form bilayers in aqueous solution but rather a type of lamellar structure, although

they are found in most membranes, especially the plasma membrane of liver cells and the chloroplasts of plants.

Within

a given species, a component of one chain-length may predominate, but other homologues are usually present.

The chain lengths of the main polyisoprenoid alcohols vary from 11 isoprene units in eubacteria, to 16 or 17 in Drosophila, 15 and 16 in yeasts,

19 in hamsters and 20 in pigs and humans.

In plants, the range is from 8 to 22 units, but some plants have an additional class of polyprenols with up to 40 units.

In tissues, polyisoprenoid alcohols can be present in the free form, esterified with acetate or fatty acids, and

phosphorylated or monoglycosylated phosphorylated (various forms), depending on species and tissue.

Polyisoprenoid alcohols per se do not form bilayers in aqueous solution but rather a type of lamellar structure, although

they are found in most membranes, especially the plasma membrane of liver cells and the chloroplasts of plants.

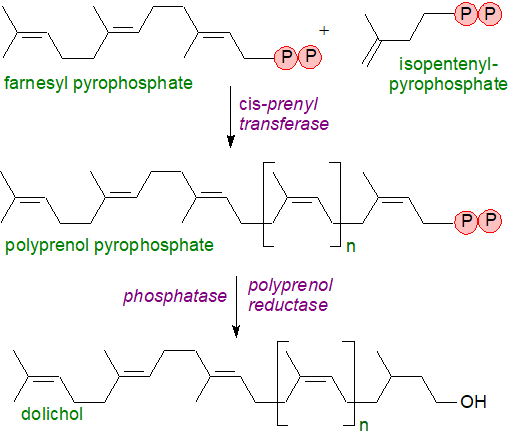

Biosynthesis of the basic building block of dolichols, i.e., isopentenyl diphosphate, follows either the mevalonate pathway or a more recently described methylerythritol phosphate pathway discussed in relation to sterol biosynthesis elsewhere on this site. Farnesyl pyrophosphate is the primary precursor in the biosynthesis of polyprenols and is the branch-point in sterol/isoprene biosynthesis (see our web page on plant sterols), depending on the nature of the organism (see a further note below). Subsequent formation of the linear prenyl chain is accomplished by cis-prenyl transferases that catalyse the condensation of isopentenyl pyrophosphate and farnesyl pyrophosphate and then the growing allylic prenyl diphosphate chain. The end products of these reactions are polyprenyl pyrophosphates, which are dephosphorylated first to polyprenol phosphate and thence to the free alcohol. Finally, a reductase has been identified from human tissues that catalyses the reduction of the double bond in position 2 to produce dolichols.

|

| Figure 6. Biosynthesis of dolichols. |

There is a family of cis-prenyl transferases in both eukaryotes and bacteria that, in addition to the synthesis of dolichols, can catalyse the formation of isoprenoid carbon skeletons from neryl pyrophosphate (C10) to natural rubber (C>10,000), as well as the polyisoprenoid phosphates, which take part in protein glycosylation as discussed in the next section.

Although polyprenols and dolichols were first considered to be simply secondary metabolites, they are now known to take part in cellular metabolism. Glycosylation of asparagine residues is the main protein modification in all three domains of life, and phosphorylated polyisoprenoids, including dolichols, are essential to this process. They are required for sexual reproduction in plants especially in relation to male gametophyte development and pollen-pistil interactions. On the other hand, free polyisoprenols have no clearly identified functions, although they can accumulate to high levels in some organisms during aging or in some disease states, and one suggestion is that free dolichol may be an antioxidant in cell membranes.

The mechanism for catabolism of dolichols is uncertain, but dolichoic acids, i.e., related molecules with a terminal carboxyl group and containing 14 to 20 isoprene units, have been isolated from the substantia nigra (neuromelanin-containing organelles - intracellular compartments of final destination for molecules not degraded by other systems) of the human brain, but they are barely detectable in pig brain.

6. Polyisoprenoid Phosphates and Glycosylation

Glycosylated phospho-polyisoprenoid alcohols are the carriers of oligosaccharide units for transfer to proteins and as activated glycosyl donors (N- and O‑linked) with conserved structures in eukaryotes, archaea and bacteria, they are substrates for glycosyl transferases for the biosynthesis of complex glycans in a similar manner to the cytosolic sugar nucleotide-diphosphate donors but in cellular regions where the latter are absent. The degree of unsaturation and chain-length of the lipid moiety are factors in the recognition by the enzymes in the next stage of glycan biosynthesis, and this is anchored in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum while the phosphate-oligosaccharide portion is located either on the cytosolic or lumenal face of the membrane.

Dolichol phosphates are produced in the final steps of dolichol synthesis de novo in the endoplasmic reticulum by dolichol kinase, which facilitates the transfer of the phosphoryl group from cytidine triphosphate; this enzyme may also re-cycle reserve pools of dolichols as phosphates. In eukaryotes, N-glycosylation begins on the cytoplasmic side of the endoplasmic reticulum with the transfer of carbohydrate moieties from nucleotide-activated sugar donors, such as uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine, onto dolichol phosphate. Then, N‑acetylglucosamine phosphate is added to give dolichol-pyrophosphate linked to N-acetylglucosamine, to which a further N‑acetylglucosamine unit is added followed by five mannose units, the last catalysed by dolichol phosphate mannose synthase, an enzyme that is also utilized for biosynthesis of GPI-anchors for proteins. The resulting dolichol-pyrophosphate-heptasaccharide is then flipped across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to the luminal face with the aid of a "flippase”, where four further mannose and three glucose residues are added to the oligosaccharide chain by means of glycosyltransferases that utilize dolichol-phospho-mannose and dolichol-phospho-glucose as donors.

In humans, the final lipid product is a C95-dolichol pyrophosphate-linked tetradecasaccharide, the oligosaccharide unit of which is transferred from the dolichol carrier onto specific asparagine residues on a developing polypeptide in the membrane. The carrier dolichol-pyrophosphate is dephosphorylated to dolichol-phosphate then diffuses or is flipped back across the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytoplasmic face. Defects in the process occur in a number of genetic diseases that include Alzheimer’s disease, dementia and prion disease.

As well as serving as monosaccharide donors for the assembly of dolichol-pyrophosphate-oligosaccharides, dolichyl-phosphate mannose and dolichyl-phosphate glucose donate their monosaccharides in many other biosynthetic pathways.

The Archaea use dolichol in their synthesis of lipid-linked oligosaccharide donors with both dolichol phosphate (Euryarchaeota) and pyrophosphate (Crenarchaeota) as carriers; these can have variable numbers of isoprene units many of which can be saturated. In the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii, a series of C55 and C60 dolichol phosphates with saturated isoprene subunits at the α- and ω-positions is involved in the glycosylation reaction of target proteins, while comparable lipid carriers of oligosaccharide units are present in methanogens. Archaea of course use isoprenyl ethers linked to glycerol as major membrane lipid components in addition to unusual carotenoids such as the C50 bacterioruberins. In many of these species, isoprenoid biosynthesis is via the 'classical' mevalonate pathway (see our web page on cholesterol), but in others, some aspects of this pathway differ.

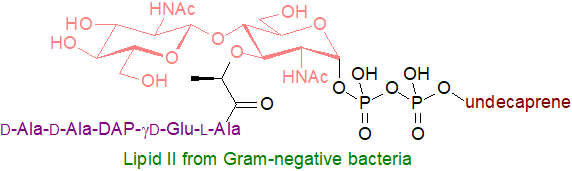

Undecaprenylphosphate: Most other bacteria use undecaprenyl-diphosphate-oligosaccharide as a glycosylation agent in the same way for the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan (the main component of most bacterial cell walls and a structure unique to bacteria), of many other cell-wall polysaccharides, including lipopolysaccharides, O-antigenic polysaccharides and capsular polysaccharides, and of N‑linked protein glycosylation in both in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Undecaprenyl phosphate (a C55 isoprenoid), sometimes referred to as bactoprenol, is the crucial lipid intermediate in which the double bonds all have the Z configuration, including in the first unit, except for the three at the ω-terminal. It is synthesised by the addition of eight units of isopentenyl pyrophosphate to farnesyl pyrophosphate, a reaction catalysed by undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase in the cytoplasm, followed by the removal of a phosphate group. Undecaprenyl phosphate is required for the synthesis and transport of glycans for external polymer formation, and glycans are covalently linked to the carrier lipid by membrane-embedded or membrane-associated enzymes using nucleotide-activated precursors. For example, the carrier lipid with GlcNAc-MurNAc-peptide monomers, i.e., as lipid II, is hydrophilic and is then transported across the cytoplasmic membrane to external sites for peptidoglycan formation and for synthesis of lipoteichoic acids and lipopolysaccharide O‑antigens.

Lipid II: Undecaprenyl diphosphate-MurNAc-pentapeptide-GlcNAc, often simply termed lipid II, is the last significant lipid intermediate (and universally conserved molecule) in the construction of the peptidoglycan cell wall, a unique protective matrix, in bacteria. Peptidoglycan biosynthesis begins in the cytosol where an integral membrane enzyme transfers a phospho-MurNAc-pentapeptide moiety from UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide to the lipid carrier undecaprenyl-phosphate to form lipid I, thereby translocating the soluble precursors to the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane. Subsequently, a further enzyme adds a GlcNAc moiety from UDP-GlcNAc to produce lipid II (Lipid II from Gram-negative bacteria has meso-diaminopimelic acid (m‑DAP) as the third amino acid of the pentapeptide chain, while in Gram-positive bacteria this is replaced by lysine). This molecule must be translocated from the cytosolic to the exterior membrane of the organism, and three different protein classes have been identified that can accomplish this, of which the best characterized is the MurJ flippase of E. coli. Once across the membrane, lipid II is cleaved to provide the MurNAc-pentapeptide-GlcNAc monomer, which undergoes polymerization and cross linking to form the complex peptidoglycan polymer that provides strength and shape to bacteria, conferring rigidity and resistance to osmotic pressure.

The undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate remaining is hydrolysed to undecaprenyl phosphate by a membrane-integrated member of the type II phosphatidic acid phosphatase family and is recycled back to the interior of the membrane by a protein UptA, to which it binds as a 1:1 complex requiring an appropriate pH and anionic phospholipids (a process that can be disrupted by some antibiotics). As the turnover rate is very high, the lipid II cycle may be the rate-limiting step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. There is some evidence that lipid II has a further function on the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane in organizing the proteins of the cytoskeleton. Because of its highly conserved structure and accessibility on the surface membrane, synthesis and transport of lipid II is a target for the development of novel antibiotics, and at present, vancomycin, a lipid II inhibitor, is a frontline antibiotic for treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other Gram-positive bacterial infections. Although some populations are becoming tolerant, unsaturated fatty acids are potent vancomycin adjuvants.

In a few prokaryotes, the membrane intermediate has a polyprenyl-monophosphate-glycan structure instead of lipid II, and undecaprenyl-phosphate-L‑4-amino-4-deoxyarabinose is required for lipid A modification in Gram-negative bacteria. There are obvious parallels with the involvement of glycosylated phospho-polyisoprenoid alcohols as carriers of oligosaccharide units for transfer to proteins and as glycosyl donors in higher organisms (see above).

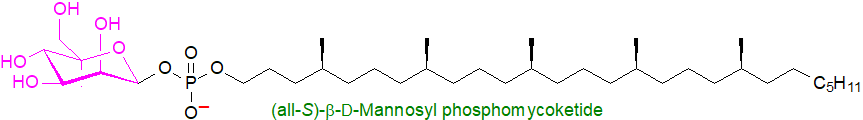

β‑D‑Mannosyl phosphomycoketide is an isoprenoid phosphoglycolipid found in the cell walls of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the lipid component of which is a C32-mycoketide, consisting of a saturated oligoisoprenoid chain with five chiral methyl branches. It acts as a potent antigen to stimulate T-cells upon presentation by CD1c protein.

7. Farnesyl Pyrophosphate and Related Compounds

Farnesyl pyrophosphate is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of sterols such as cholesterol, and it is the donor of the farnesyl group in the biosynthesis of dolichols and polyprenols (see above) as well as for the isoprenylation of many proteins (see the web page on proteolipids). It is known to be a mediator of various metabolic reactions via an interaction with a specific receptor and is synthesised by two successive phosphorylation reactions of farnesol. It has been identified as danger signal that triggers acute cell death and neuron loss in stroke, and inhibition of its synthesis alleviates cardiomyopathy in diabetic rats.

Presqualene diphosphate is unique among the isoprenoid phosphates in that it contains a cyclopropylcarbinyl ring. In addition to being a biosynthetic precursor of squalene and thence of cholesterol and other triterpenoids, it is a natural anti-inflammatory agent, which inhibits phospholipase D and the generation of superoxide anions in neutrophils.

Recommended Reading

- Braasch-Turi, M.M., Koehn, J.T. and Crans, D.C. Chemistry of lipoquinones: properties, synthesis, and membrane location of ubiquinones, plastoquinones, and menaquinones. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23, 12856 (2022); DOI.

- Chehade, M.H. and 14 others. A soluble metabolon synthesizes the isoprenoid lipid ubiquinone. Cell Chem. Biol., 26, 482-492.e7 (2019); DOI.

- Dupuy, M., Bondonno, N.P., Pokharel, P., Linneberg, A., Levinger, I., Schultz, C., Hodgson, J.M. and Sim, M. Vitamin K: metabolism, genetic influences, and chronic disease outcomes. Food Sci. Nutr., 13, e70431 (2025); DOI.

- Eichler, J. and Guan, Z. Lipid sugar carriers at the extremes: The phosphodolichols Archaea use in N-glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Lipids, 1862, 589-599 (2017); DOI.

- Faulkner, R. and Jo, Y. Synthesis, function, and regulation of sterol and nonsterol isoprenoids. Front. Mol. Biosci., 9, 1006822 (2022); DOI.

- Franza, T. and Gaudu, P. Quinones: more than electron shuttles. Res. Microbiol., 173, 103953 (2022); DOI.

- Grabińska, K.A., Park, E.J. and Sessa, W.C. cis-Prenyltransferase: new insights into protein glycosylation, rubber synthesis, and human diseases. J. Biol. Chem., 291, 18582-18590 (2016); DOI.

- Guile, M.D., Jain, A., Anderson, K.A. and Clarke, C.F. New insights on the uptake and trafficking of coenzyme Q. Antioxidants, 12, 1391 (2023); DOI.

- Gutbrod, K., Romer, J. and Dörmann, P. Phytol metabolism in plants. Prog. Lipid Res., 74, 1-17 (2019); DOI.

- Havaux, M. Plastoquinone in and beyond photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci., 25, 1252-1265 (2020); DOI.

- Kumar, S., Mollo, A., Kahne, D. and Ruiz, N. The bacterial cell wall: from lipid II flipping to polymerization. Chem. Rev., 122, 8884-8910 (2022); DOI.

- Myneni, V. and Mezey, E. Regulation of bone remodeling by vitamin K2. Oral Diseases, 23, 1021-1028 (2017); DOI.

- Ninkuu, V., Zhang, L., Yan, J.P., Fu, Z.C., Yang, T.F. and Zeng, H.M. Biochemistry of terpenes and recent advances in plant protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22, 5710 (2021); DOI.

- Nowicka, B., Trela-Makowej, A., Latowski, D., Strzalka, K. and Szymanska, R. Antioxidant and signaling role of plastid-derived isoprenoid quinones and chromanols. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22, 2950 (2021); DOI.

- Sadler, R.A., Shoveller, A.K., Shandilya, U.K., Charchoglyan, A., Wagter-Lesperance, L., Bridle, B.W., Mallard, B.A. and Karrow, N.A. Beyond the coagulation cascade: vitamin K and its multifaceted impact on human and domesticated animal health. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol., 46, 7001-7031 (2024); DOI.

- Surmacz, L. and Swiezewska, E. Polyisoprenoids - secondary metabolites or physiologically important superlipids? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 407, 627-632 (2011); DOI.

- Wang, Y., Lilienfeldt, N. and Hekimi, S. Understanding coenzyme Q. Physiol. Rev., 114, 1533-1610 (2024); DOI.

- Workman, S.D. and Strynadka, N.C.J. A slippery scaffold: synthesis and recycling of the bacterial cell wall carrier lipid. J. Mol. Biol., 432, 4964-4982 (2020); DOI.

- Xu, J.J., Hu, M., Yang, L. and Chen, X.Y. How plants synthesize coenzyme Q. Plant Commun., 3, 100341 (2022); DOI.

|

© Author: William W. Christie |  |

|

| Contact/credits/disclaimer | Updated: November 2025 | ||

© The LipidWeb is open access and fair use is encouraged but not text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.